GAAP vs. Tax Depreciation for CRE Components

Understanding GAAP and Tax Depreciation:

GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and tax depreciation differ in how commercial real estate (CRE) assets are depreciated. GAAP focuses on matching expenses to an asset’s useful life, often using a straight-line method. Tax depreciation, on the other hand, uses IRS-mandated rules like the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS), which allows faster deductions upfront. These differences impact financial reporting, tax planning, and cash flow strategies.

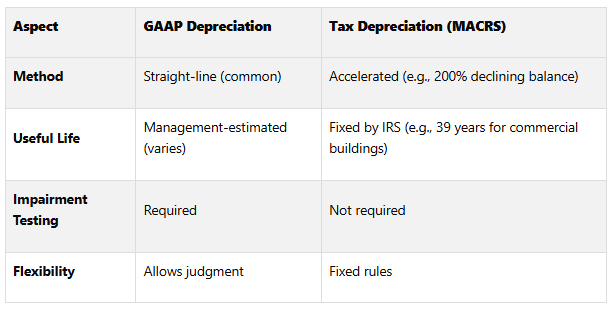

Key Differences:

Methodology: GAAP uses estimated useful lives and often requires impairment testing. Tax depreciation applies fixed recovery periods and accelerated methods like declining balance.

Timing: GAAP spreads costs evenly, while tax depreciation front-loads expenses for earlier tax benefits.

Flexibility: GAAP allows professional judgment in asset valuation; tax rules are rigid and standardized.

Quick Comparison:

Why It Matters:

These differences create temporary mismatches in income and tax reporting, requiring careful tracking. For CRE professionals, understanding both systems is essential to optimize tax savings, maintain compliance, and present accurate financial statements.

Depreciation Accounting (MACRS vs GAAP Book Depreciation Effect On Taxable Income)

GAAP Component Depreciation Rules

Before diving into tax depreciation methods, it’s important to first understand the flexibility GAAP provides when it comes to component depreciation.

GAAP Depreciation Methods and Standards

Under US GAAP, component depreciation is permitted but not mandatory. Commercial real estate (CRE) firms have the option to depreciate major parts of a building separately. A component is considered a tangible asset that can be individually identified and depreciated over its own useful life, provided it delivers economic benefits for more than one year. When choosing to apply component depreciation, a company must establish its accounting policy regarding the level of detail required at the time it acquires or constructs a long-lived asset.

Take, for example, a commercial office building. It might have separate depreciation schedules for its HVAC system, structural frame, and elevators. GAAP requires that the total capitalized cost of the building be allocated to its components. This can be done using specific identification or a relative fair value approach. If those methods aren’t feasible, a proxy like square footage may be used. To simplify, similar components can be grouped together. It’s also worth noting that most CRE assets rely on the straight-line method, which ensures consistent expense recognition over time.

Impairment Testing Requirements

Determining an asset’s useful life involves evaluating several factors, including usage patterns, regulatory requirements, historical performance, and economic considerations like potential obsolescence. GAAP defines useful life as the time during which an asset is expected to contribute to future cash flows. Companies are required to reassess these estimates periodically, especially if conditions suggest the original assumptions about useful life are no longer accurate. For CRE assets, maintenance expenses and other operational factors may also play a role in this evaluation.

Depreciation and Revenue Recognition

Under ASC 842, GAAP specifies that when a component is replaced, the new part should be capitalized (if it meets the criteria), while the net book value of the old component must be written off as an expense. Additionally, component depreciation impacts multiple financial statements - it must be reflected in the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. Salvage value estimates should also take into account all costs associated with realizing that value. These detailed GAAP rules provide a foundation for understanding how tax depreciation methods differ when applied to CRE components.

Tax Depreciation Methods for CRE

Tax depreciation operates under strict federal guidelines, which differ significantly from the more flexible methods allowed by GAAP. The IRS enforces specific rules and timelines, creating a structured approach to depreciation for commercial real estate (CRE).

MACRS System Overview

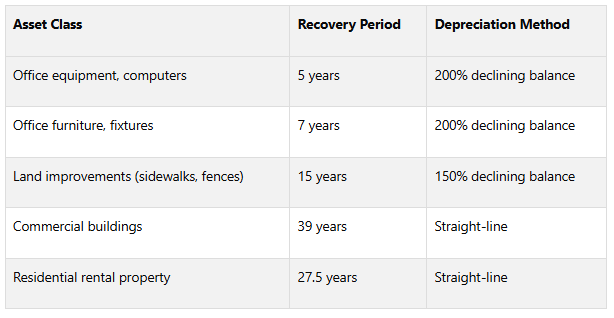

The IRS requires CRE owners to use the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) for properties placed in service after 1986. This framework organizes assets into predefined classes with fixed depreciation periods, ensuring consistency across the board.

MACRS includes two systems: the General Depreciation System (GDS) and the Alternative Depreciation System (ADS). Most CRE owners prefer GDS, as it allows for faster depreciation in the early years of an asset's life. However, ADS must be used in certain cases, such as for farming properties or assets located outside the U.S..

The MACRS system assigns specific recovery periods and methods based on property type:

Commercial buildings: Depreciated over 39 years using the straight-line method.

Residential rental properties: Depreciated over 27.5 years using the straight-line method.

Land improvements (e.g., sidewalks, fences, landscaping): Depreciated over 15 years using the 150% declining balance method.

Personal property components (e.g., office equipment, fixtures): Depreciated over 5 or 7 years using the 200% declining balance method.

"Depreciation is the recovery of the cost of the property over a number of years. You deduct a part of the cost every year until you fully recover its cost." - IRS

One key feature of MACRS is its acceleration mechanism, which provides larger deductions in the early years of an asset’s life. This can significantly improve cash flow for property owners. For 2024, 60% bonus depreciation is available for qualified assets, though this percentage will decrease annually until it phases out in 2027.

Tax Rules vs. GAAP Requirements

Unlike GAAP, which allows for professional judgment in estimating useful lives and choosing depreciation methods, tax depreciation follows standardized rules. The IRS sets recovery periods and methods for each asset class, leaving no room for subjective interpretation.

For example, while GAAP permits companies to select methods like straight-line or declining balance based on how an asset generates economic benefits, tax depreciation assigns these methods automatically. Additionally, tax depreciation does not require impairment testing. Assets continue to depreciate on schedule, regardless of changes in market value, unlike GAAP, which demands periodic assessments for permanent value declines.

These differences often lead to temporary timing mismatches between book and tax depreciation. A building component might be fully depreciated for tax purposes while still holding significant value on GAAP financial statements - or vice versa. These mismatches can create notable variations between reported income and taxable income, requiring careful tracking to ensure accurate financial reporting and tax compliance.

Component Allocation for Tax Purposes

The IRS mandates that property owners break down building costs into specific asset classes, a process known as cost segregation. This involves identifying components that qualify for shorter depreciation periods, which can lead to significant tax savings.

For improvements made after construction, tax rules distinguish between repairs (which are immediately deductible) and capital improvements (which must be depreciated). These classifications often differ from GAAP's capitalization thresholds, adding another layer of complexity.

Property owners can also take advantage of the de minimis safe harbor, which allows for the immediate expensing of low-cost items. For 2024, this provision permits deductions for items costing up to $1,220,000 under Section 179, though the benefit phases out for businesses spending more than $3,050,000 annually. It’s crucial to establish and document capitalization policies before the tax year begins to comply with these rules.

Navigating these regulations requires specialized knowledge to ensure compliance while maximizing tax benefits. Unlike GAAP, which allows for flexibility and professional judgment, tax depreciation demands strict adherence to detailed IRS rules. Staying updated on legislative changes and IRS guidance is essential for optimizing financial outcomes in CRE.

Transform Your Real Estate Strategy

Access expert financial analysis, custom models, and tailored insights to drive your commercial real estate success. Simplify decision-making with our flexible, scalable solutions.

GAAP vs Tax Depreciation Differences

GAAP and tax depreciation differ significantly in how they estimate asset lifespans and allocate expenses, which directly affects financial reporting and cash flow strategies.

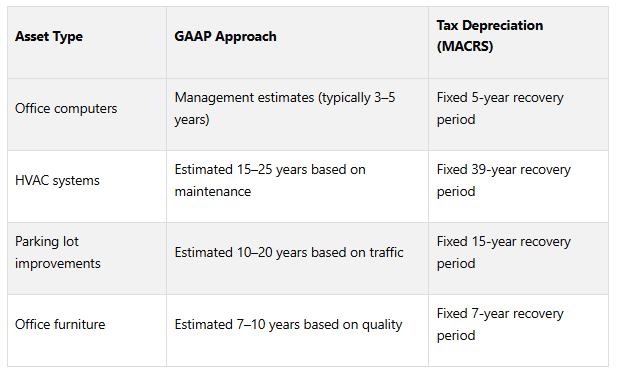

Methods and Useful Lives Comparison

The primary distinction lies in how each system determines asset lifespans and depreciation methods. Under GAAP, management estimates an asset's useful life by considering factors like technological advancements, usage patterns, and maintenance schedules. For example, a building component such as an HVAC system might be depreciated over varying periods depending on its anticipated use and upkeep. In contrast, tax depreciation follows fixed recovery periods set by the Internal Revenue Code, leaving no room for managerial discretion. For instance, a computer system is always classified as five-year property under MACRS, regardless of how it is used.

GAAP typically uses the straight-line depreciation method, spreading the cost evenly over the asset's estimated life. On the other hand, tax depreciation employs accelerated methods, which allow for larger deductions in the earlier years of an asset's life, offering immediate tax benefits.

These differences in methodology lead to further distinctions in how impairments and expense timing are handled.

Impairment and Adjustment Differences

Beyond depreciation methods, impairment adjustments highlight another key difference between GAAP and tax depreciation. Under GAAP, assets undergo impairment testing whenever specific events suggest their market value may have dropped below their book value. If such a decline occurs, an impairment loss must be recorded immediately to ensure asset values are not overstated. Tax law, however, does not allow for routine impairment adjustments. Instead, assets continue depreciating on their predetermined schedules, regardless of market fluctuations. This creates temporary differences between book and tax values when impairments are recognized under GAAP but not reflected for tax purposes.

GAAP's approach is guided by the principle of conservatism, which aims to avoid overestimating profits and asset values. In contrast, tax laws generally only permit deductions for losses when they are fixed and measurable.

Revenue and Expense Timing Differences

Another area of divergence is the timing of revenue recognition and expense allocation. GAAP aligns expenses with the economic benefits provided by an asset, ensuring a clear connection between costs and revenues. Tax depreciation, however, prioritizes accelerated deductions to minimize current-year tax liabilities. Tax rules also encourage faster recognition of gross income while delaying expense deductions until specific criteria are met. This often results in higher book income compared to taxable income in the early years, with these differences reversing over time.

Tax provisions like bonus depreciation and Section 179 expensing further amplify these timing mismatches. These provisions allow businesses to immediately expense qualifying equipment for tax purposes, even though the same assets are depreciated over their useful lives under GAAP. Such discrepancies necessitate deferred tax accounting to reconcile cash flow impacts and financial ratios.

Grasping these differences is essential for navigating loan covenants, managing investor expectations, and making informed strategic decisions. For instance, an asset that appears profitable under GAAP might yield tax losses, or vice versa, creating complexities in financial planning and reporting.

Impact on CRE Financial Analysis

The differences between GAAP and tax depreciation play a significant role in how financial analysis is conducted in the commercial real estate (CRE) sector. These variations influence balance sheets, income statements, and investor reporting, making it essential for CRE professionals to grasp their implications. A solid understanding helps navigate reporting complexities and supports better decision-making.

Financial Statement Effects

GAAP and tax depreciation discrepancies change how financial statements reflect a company's performance. Here's how these differences manifest:

Balance Sheet Adjustments

Recent GAAP lease accounting rules require companies to report a Right-of-Use (ROU) asset and a lease obligation. This approach alters balance sheets compared to tax accounting, which focuses on cash-based rent expenses.

Timing Differences in Income Statements

With GAAP, rent expenses combine ROU asset amortization and lease interest, leading to higher initial costs that taper off over time. In contrast, tax accounting maintains consistent cash-based rent recognition throughout the lease period.

Depreciation and Capitalization Variances

Tax rules allow accelerated depreciation methods, including bonus depreciation of up to 100% of an asset's cost. These methods can significantly differ from GAAP, which spreads depreciation over an asset's useful life. Tax accounting also permits higher upfront expensing thresholds (up to $2,500 or $5,000), whereas GAAP typically caps these thresholds at $1,000 to $2,500. These differences create temporary variances, impacting the comparability of financial statements.

These variations influence more than just the numbers - they also affect compliance with loan covenants and investor relations.

Loan Covenants and Investor Relations

Depreciation methods directly impact key metrics like EBITDA, which lenders and investors closely monitor.

EBITDA Considerations

Most banks and investors require GAAP-based financial statements, making it critical to understand how depreciation impacts EBITDA. As Dustin Minton, CPA, MBA, and director of assurance and business advisory services at GBQ CPAs, explains:

"It is also essential to understand the impact each basis of accounting can have on your EBITDA and related financial debt covenants." – Dustin Minton, CPA

While GAAP depreciation is often added back to EBITDA, tax-based accounting with higher upfront expenses can negatively affect covenant calculations.

Lease Accounting Adjustments

For companies affected by lease accounting changes, a GAAP carve-out for operating leases might help mitigate significant impacts on financial ratios.

Investor Communication Challenges

Dual reporting systems can complicate how companies communicate with investors. GAAP's reliance on estimates and occasional third-party valuations may increase compliance costs but often provides a clearer picture of a company's economic reality compared to tax-basis reporting.

Beyond these financial and investor impacts, depreciation differences also influence tax planning strategies.

Tax Planning and Compliance

Effective tax planning in CRE requires aligning GAAP reporting with tax strategies. Key areas to consider include:

Strategic Tax Planning

Assessing whether current leases fully utilize available tax benefits - or if another party might better leverage these advantages - is a critical part of strategic planning.

Compliance Challenges

Managing both GAAP and tax accounting systems adds complexity. While tax compliance is generally straightforward, GAAP requires more judgment and may involve third-party valuations, leading to additional costs and non-cash expenses that need separate tracking.

Optimizing Timing Strategies

Companies can use accelerated tax depreciation to gain immediate tax relief while relying on GAAP depreciation for financial reporting that better reflects economic conditions. However, this dual approach demands robust tracking systems and expert oversight.

Professional Guidance

The Fractional Analyst offers valuable expertise in reconciling GAAP and tax depreciation differences. Their team helps CRE professionals improve reporting accuracy, ensure covenant compliance, and optimize tax strategies, aligning financial practices with both regulatory and strategic goals.

For companies considering a GAAP conversion, planning ahead and setting clear timelines for affected accounting areas is crucial.

Conclusion

The discussions above highlight the importance of aligning depreciation methods to balance financial reporting and tax planning effectively. The differences between GAAP and tax depreciation significantly influence financial statements, investor relations, and tax strategies, making it crucial for CRE professionals to grasp these distinctions. While both systems serve unique purposes, they also have varying impacts on reporting requirements and tax optimization.

Key Points to Remember

The differences between GAAP and tax depreciation play a major role in managing CRE finances. Here’s how they differ:

GAAP Depreciation: Assets are depreciated over their estimated useful lives, with periodic impairment testing. For example, under GAAP, a $1 million office building would depreciate over 39 years, resulting in annual depreciation of around $25,000.

Tax Depreciation: Based on statutory lives under the Internal Revenue Code (MACRS), tax depreciation allows accelerated, front-loaded deductions, without requiring impairment testing.

While GAAP uses a straight-line approach for revenue recognition, tax accounting accelerates deductions, creating differences in cash flow and financial metrics. Tax depreciation enhances early cash flow through accelerated deductions, whereas GAAP’s impairment testing can lead to earlier recognition of losses, affecting reported earnings and asset values. Tax systems, on the other hand, defer loss recognition until they are fixed.

Leveraging Professional Tools and Expertise

Navigating the complexities of dual accounting systems requires advanced tools and expert support. The Fractional Analyst provides tailored solutions for CRE professionals, offering both hands-on financial analysis and self-service tools through CoreCast. These services help ensure accurate allocation of components, compliance with accounting standards, and effective tax planning.

Investing in professional guidance and modern financial tools can improve reporting accuracy, strengthen stakeholder confidence, and refine tax strategies. Ultimately, these efforts can boost the financial performance of CRE properties while ensuring compliance with evolving tax laws and GAAP standards.

FAQs

-

The way GAAP depreciation and tax depreciation are handled can have a noticeable effect on the financial statements of a commercial real estate (CRE) company. Under GAAP, the straight-line method is commonly used, which spreads depreciation evenly over the asset's useful life. This method ensures steady expense recognition, directly impacting net income and how assets are valued on the balance sheet.

On the other hand, tax depreciation often uses accelerated methods such as MACRS (Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System). These methods front-load depreciation expenses, resulting in higher deductions during the early years of an asset's life. While this reduces taxable income, it can create differences in net income and asset values when compared to GAAP reporting.

Recognizing these differences is essential for precise financial analysis, smart tax planning, and making informed strategic decisions. They can also affect key factors like investor confidence, borrowing potential, and overall business performance in the CRE sector.

-

Using component depreciation in commercial real estate (CRE) under GAAP offers some clear benefits. By dividing a property into individual components - like HVAC systems or roofing - depreciation expenses can be allocated more precisely. This approach provides more detailed financial reporting and can offer valuable insights for managing assets effectively.

That said, there are challenges to consider. Component depreciation often requires meticulous record-keeping, which can drive up administrative costs. Plus, since GAAP doesn’t require this method, applying it inconsistently across properties might create discrepancies in financial statements. Carefully weighing these pros and cons is key to determining if this approach fits your CRE strategy.

-

When it comes to managing taxes and staying compliant, commercial real estate professionals need a thoughtful approach to asset purchases and depreciation methods. For tax purposes, methods like accelerated depreciation, including MACRS or bonus depreciation, can offer substantial short-term savings. On the other hand, straight-line depreciation is often preferred for GAAP reporting because it provides consistency and simplifies handling temporary differences between financial and tax records.

Keeping detailed records and ensuring that depreciation schedules align with both IRS and GAAP guidelines is essential for staying compliant. By carefully managing these differences, professionals can take advantage of tax benefits while adhering to regulatory requirements.