GAAP vs. Tax Rules for Depreciation Start Dates

When does depreciation start? It depends on the rules you follow - GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) or IRS tax regulations. Both define "placed in service" differently, which impacts your financial reporting and taxes. For commercial real estate professionals, understanding these differences is crucial to avoid compliance issues and optimize financial strategies.

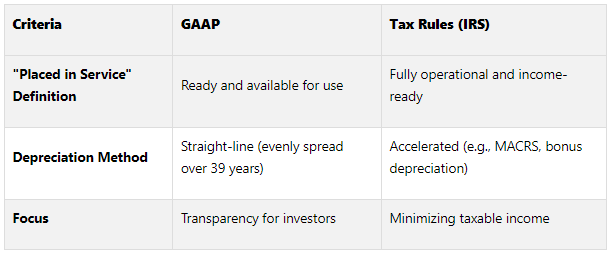

Key Differences Between GAAP and Tax Depreciation:

GAAP: Depreciation begins when the property is "ready and available for use", even if it’s not actively in use. Uses straight-line depreciation (39 years for commercial buildings).

Tax Rules: Stricter. The property must be fully operational (e.g., permits obtained, ready to generate income). Uses accelerated methods like MACRS, allowing bigger deductions upfront.

Why It Matters:

For Investors and Lenders: GAAP compliance builds trust and supports financing.

For Taxes: Proper start dates reduce taxable income and avoid penalties.

Quick Comparison:

Understanding these differences helps you manage compliance, financial reporting, and tax planning effectively.

Depreciation Accounting (MACRS vs GAAP Book Depreciation Effect On Taxable Income)

GAAP Rules for Depreciation Start Dates

Understanding how GAAP handles depreciation start dates is essential when comparing it to tax regulations. GAAP establishes clear guidelines for when depreciation should begin, though these rules are sometimes misunderstood. The main principle is straightforward: depreciation starts when an asset is ready and available for its intended use.

How GAAP Defines 'Placed in Service'

Under GAAP standards, depreciation begins once an asset is deemed "ready and available for a specific use". This doesn’t mean the asset has to be actively used or generating income. For instance, if a newly constructed office building receives its certificate of occupancy in December, it’s considered placed in service at that time - even if it remains vacant until a tenant is secured later. The date the asset is placed in service marks the starting point for depreciation. Companies often favor an earlier placed-in-service date because it enables them to record depreciation expenses sooner.

Standard Depreciation Methods in GAAP

GAAP commonly uses the straight-line depreciation method for commercial real estate. This method spreads the asset's cost evenly over its useful life, which for non-residential buildings typically means a 39-year depreciation schedule. Identifying the correct placed-in-service date is a crucial first step in this process. Once established, depreciation continues until the asset is either fully depreciated or removed from service.

GAAP Impairment Review Requirements

Beyond determining when depreciation begins, GAAP also mandates periodic impairment reviews for long-term assets like commercial real estate. These reviews ensure that an asset’s carrying value doesn’t exceed its recoverable amount, safeguarding against changes in market conditions. Additionally, many lenders and real estate investors require GAAP-compliant financial statements before extending financing. By combining regular impairment reviews with accurate depreciation start dates, companies can ensure their financial statements reflect the property’s value accurately over time. These practices under GAAP create a foundation for later exploring how tax rules differ in their approach.

Tax Rules for Depreciation Start Dates

While GAAP provides a framework for determining depreciation timing, the IRS sets stricter standards that directly affect tax deductions. Understanding these rules is crucial for ensuring compliance while maximizing deductions. Let’s break down how the IRS defines "placed in service" and explore its impact on tax depreciation.

How the IRS Defines "Placed in Service"

According to IRS guidelines, depreciation begins when a property is ready and available for its intended use. Although this may sound similar to GAAP, the IRS applies a more rigorous standard. For example, when it comes to commercial buildings, the IRS requires clear benchmarks to confirm readiness. These include obtaining necessary licenses and permits, completing essential tests, transferring control to the taxpayer, and starting regular operations. Without meeting these conditions, the property is not considered "placed in service" for tax purposes.

Accelerated Tax Depreciation Methods

Unlike GAAP’s common use of straight-line depreciation, the IRS allows for faster depreciation through the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). This system categorizes business assets into specific classes with defined recovery periods. For instance:

Non-residential commercial properties: Depreciated over 39 years.

Residential rental properties: Depreciated over 27.5 years.

Additionally, the tax code offers incentives to further accelerate deductions. Bonus depreciation, for example, is phasing down over the next few years - 60% in 2024, 40% in 2025, 20% in 2026, and eliminated by 2027. Meanwhile, Section 179 expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct up to $1,250,000 starting in 2025, though phase-out limits apply.

Why "Actual Use" Matters for Tax Purposes

The IRS takes a stricter stance than GAAP by requiring evidence of actual operational use before a property is considered placed in service. For rental properties, this means meeting local housing codes and demonstrating efforts to generate income. This distinction has significant tax implications. If depreciation deductions aren’t claimed, the IRS will still calculate taxable gain as if those deductions had been taken. Moreover, the chosen depreciation method becomes locked once the property is placed in service.

For example, in 2019, approximately 10.6 million Americans reported rental income. Missteps in determining the placed-in-service date could lead to costly tax consequences. Consulting a tax professional can help ensure compliance and optimize your tax strategy.

In short, while the IRS definition of "placed in service" may resemble GAAP on the surface, its application often demands stricter proof of operational readiness.

Transform Your Real Estate Strategy

Access expert financial analysis, custom models, and tailored insights to drive your commercial real estate success. Simplify decision-making with our flexible, scalable solutions.

Main Differences Between GAAP and Tax Depreciation Start Dates

Building on the earlier explanations, let’s dive into how GAAP and IRS rules differ in practice and how these differences influence both financial reporting and tax compliance. While both systems use the term "placed in service", their definitions and applications can lead to noticeably different outcomes for businesses.

Different 'Placed in Service' Definitions

GAAP and IRS rules may seem similar on the surface, but their practical interpretations diverge. Under GAAP, depreciation can begin as soon as an asset is ready and available for use, even if it hasn’t been actively used yet. On the other hand, the IRS requires the asset to be fully operational - often verified by a certificate of occupancy or complete installation - before depreciation starts. This distinction becomes especially clear with assets like equipment that remain stored before installation.

Effects on Financial Statements and Tax Returns

The timing difference in when depreciation begins has a direct impact on pretax earnings and tax liabilities. GAAP’s earlier depreciation start reduces asset values and net income sooner, creating a deferred tax liability when compared to tax returns. Beyond that, GAAP and tax rules also differ in how they recognize rental income and expenses.

Here’s a practical example: A company buys a delivery van for $120,000 on January 1, 2023. Under GAAP, using the straight-line method, the annual depreciation would be $24,000 over the van’s 5-year useful life. For tax purposes, if a 25% declining balance method is allowed, the first-year depreciation could be $30,000. This results in a temporary $6,000 difference, which reduces taxable income and creates a deferred tax liability. These differences highlight why maintaining separate depreciation schedules is crucial for compliance.

Common Compliance Problems

These timing discrepancies don’t just affect financial outcomes - they also create compliance headaches. Using different depreciation methods can lead to classification errors, reconciliation challenges, and increased audit risks. For large corporations, the stakes are even higher. In 2019, 50% of companies with assets exceeding $20 billion were audited by the IRS, compared to a corporate audit rate of just 0.7% overall.

To stay compliant and avoid penalties, businesses should adopt a disciplined approach. This includes maintaining separate depreciation schedules for financial and tax reporting and reconciling the differences annually.

“Understanding the distinction between accounting depreciation and tax depreciation is essential for accurate reporting, regulatory compliance, and strategic financial planning.”

How This Affects Commercial Real Estate Financial Analysis

The differences in depreciation start dates between GAAP and tax accounting have a direct impact on financial analysis in commercial real estate. These variations influence how investors and lenders assess property performance, cash flow, and investment returns. Building on the rules mentioned earlier, these differences ripple through earnings, cash flow, and the way stakeholders interpret financial data.

Impact on Earnings and Cash Flow Analysis

Timing differences in depreciation play a significant role in shaping key financial metrics that drive investment decisions. GAAP uses a straight-line method, which spreads depreciation evenly over the asset's useful life. On the other hand, MACRS (used for tax purposes) accelerates depreciation, front-loading deductions and reducing taxable income in the early years.

GAAP relies on an accrual-based system, recognizing revenues when earned and expenses when incurred - regardless of actual cash flow timing. In contrast, tax accounting often adopts a cash or modified cash basis, resulting in notable differences in reported profitability.

Take, for example, a commercial building with a cost of $390,000 and no salvage value. Using GAAP's straight-line method, the annual depreciation would be $10,000 over 39 years. However, under MACRS, the same property might see higher deductions in the initial years, lowering taxable income but not necessarily reflecting the asset's true economic depreciation.

When dealing with multiple properties, these timing differences can complicate cash flow analysis. GAAP aims to provide a clear picture of a company's financial health, while tax accounting focuses on determining taxable income. As a result, the same property portfolio might show different cash flow patterns depending on the accounting method used.

What to Tell Investors and Lenders

Clear communication with stakeholders is critical given the valuation differences between GAAP and tax accounting. Lenders typically focus on GAAP-based financial metrics - like debt-to-equity ratios, interest coverage ratios, and EBITDA - to evaluate financial strength. They also need to understand how tax depreciation impacts cash flow and tax obligations.

Profitability can vary significantly between GAAP and tax accounting due to differences in revenue and expense recognition timing. For investors, especially those comparing multiple opportunities, consistent and comparable data is essential. This is why GAAP compliance is often required for larger transactions and institutional investors.

Key points to communicate include:

How depreciation methods affect reported net income versus actual cash available for distribution

Why GAAP financials are preferred by investors, as tax-basis statements may obscure true cash flow

The effects of accelerated tax depreciation on short-term cash flow and long-term asset valuation

How The Fractional Analyst Can Help

Navigating these complexities requires expertise, and The Fractional Analyst offers tailored solutions to address these challenges. By reconciling GAAP and tax depreciation, we help optimize compliance and returns. As mentioned earlier, differing depreciation start dates impact financial metrics, making expert guidance essential for aligning reporting perspectives.

Our underwriting services account for both GAAP and tax depreciation, providing a complete view of how timing differences influence investment returns. Through our CoreCast platform, real estate professionals gain access to financial models that calculate depreciation under both methods, simplifying reconciliation and maintaining separate schedules for financial and tax reporting.

For investor and lender communications, we create customized reports that clearly explain how depreciation affects key metrics. This transparency ensures stakeholders understand why a property might show different performance metrics depending on the accounting framework.

Additionally, our asset management services include ongoing monitoring of how depreciation timing impacts portfolio performance. Whether you need GAAP-compliant statements for institutional investors or tax-focused projections for ownership decisions, our team is equipped to guide you through both requirements effectively.

Conclusion

Main Points Summary

GAAP and tax depreciation rules play distinct roles in shaping the financial landscape of commercial real estate. GAAP relies on straight-line depreciation to provide an accurate, long-term view of asset value decline, offering stakeholders a reliable financial snapshot. On the other hand, tax rules like MACRS focus on accelerated deductions, reducing taxable income in the earlier years of ownership. These two approaches influence every aspect of financial management in commercial real estate. GAAP’s accrual-based framework uncovers potential financial challenges and aids strategic decisions, while tax accounting’s cash-oriented focus may give a narrower perspective of a firm's overall financial health.

For residential and commercial properties, US GAAP applies depreciation schedules of 27.5 and 39 years, respectively. Meanwhile, MACRS allows faster depreciation for specific components, such as land improvements. While these tax benefits can optimize cash flow, they require careful financial planning to ensure compliance with both frameworks. Navigating these differences is essential for aligning financial reporting with broader strategic goals.

What CRE Professionals Should Do Next

To effectively manage the financial nuances of depreciation, commercial real estate professionals need a dual approach. Start by mastering the differences between GAAP and tax depreciation. Then, implement systems that support both frameworks. This includes producing GAAP-compliant financial statements like income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements on a regular basis.

Maintain detailed records of property purchase prices, acquisition costs, and improvements. These records are critical for accurate depreciation calculations and can protect against IRS audit risks. Leveraging property management accounting software or asset tracking tools can streamline depreciation calculations under both GAAP and tax systems, ensuring compliance and efficiency.

Collaborate with real estate tax experts to navigate the complexities of these dual frameworks. These professionals can help maximize depreciation deductions while ensuring compliance with both GAAP and tax regulations. Conducting cost segregation studies can also pinpoint property components eligible for shorter depreciation schedules, boosting tax savings without impacting GAAP reporting.

For larger portfolios or when internal resources are stretched, consider working with specialized financial service providers. For example, The Fractional Analyst offers tailored financial solutions that reconcile GAAP and tax depreciation, providing underwriting services and customized reports for investors and lenders. Through tools like the CoreCast platform, real estate professionals can access financial models that simplify depreciation calculations across both frameworks, ensuring compliance and improving returns.

FAQs

-

The term "placed in service" is crucial when it comes to depreciation and financial reporting in commercial real estate. According to GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles), this refers to the point when an asset is ready and available for its intended use. This designation influences how the asset is recorded in financial statements. On the other hand, for IRS tax purposes, the "placed in service" date marks when depreciation begins, which directly affects the timing and size of tax deductions.

These differing interpretations can lead to variations in reported income, asset valuations, and tax strategies. For instance, while GAAP prioritizes financial accuracy to provide clarity for stakeholders, the IRS definition may allow for earlier depreciation, offering potential tax advantages. Grasping these differences is key for making informed financial decisions, ensuring compliance, and optimizing investments in the U.S. commercial real estate market.

-

The decision between GAAP and tax rules for calculating depreciation in commercial real estate has a direct impact on financial reporting, tax obligations, and cash flow management. Under GAAP, depreciation is usually calculated using the straight-line method, which spreads the expense evenly across the asset's useful life. This method provides consistent expense recognition but can result in higher taxable income during the earlier years of ownership.

On the other hand, tax rules often favor accelerated methods, such as the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). These methods allow for larger depreciation deductions in the initial years, which can lower taxable income and reduce taxes owed in the short term, leading to better cash flow early on. However, this approach means fewer depreciation deductions - and therefore higher taxable income - in later years.

Your choice of method also affects financial metrics, how assets are valued, and how investors view your financial performance. GAAP depreciation provides a more stable representation of long-term financial health, while tax depreciation is geared toward maximizing immediate tax savings. When deciding which method to use, it’s important to align the choice with your financial objectives, tax planning strategy, and reporting needs.

-

To navigate the differences between GAAP and IRS depreciation rules, it’s essential for commercial real estate professionals to grasp the key distinctions. For instance, the IRS mandates a 39-year straight-line depreciation for commercial properties. On the other hand, GAAP provides more flexibility, allowing for methods like straight-line or accelerated depreciation based on specific circumstances.

To maximize financial advantages, align your tax strategies with IRS guidelines to leverage deductions, such as accelerated depreciation when applicable. Simultaneously, ensure your financial reports adhere to GAAP standards to maintain clarity and accuracy. Regularly consulting with tax and accounting professionals can help you stay informed about changing regulations and ensure your strategies remain compliant and effective.